This article by Neal Buccino was featured in Rutgers Today on February 25, 2020.

Decades before the civil rights era, the “forerunner generation” paved the way for desegregation

In a new book in the Scarlet and Black project, Rutgers University continues to examine its historical relationship to race, slavery and disenfranchisement, telling the story of the university’s first black students, who were pioneers treated as outcasts on their own campus.

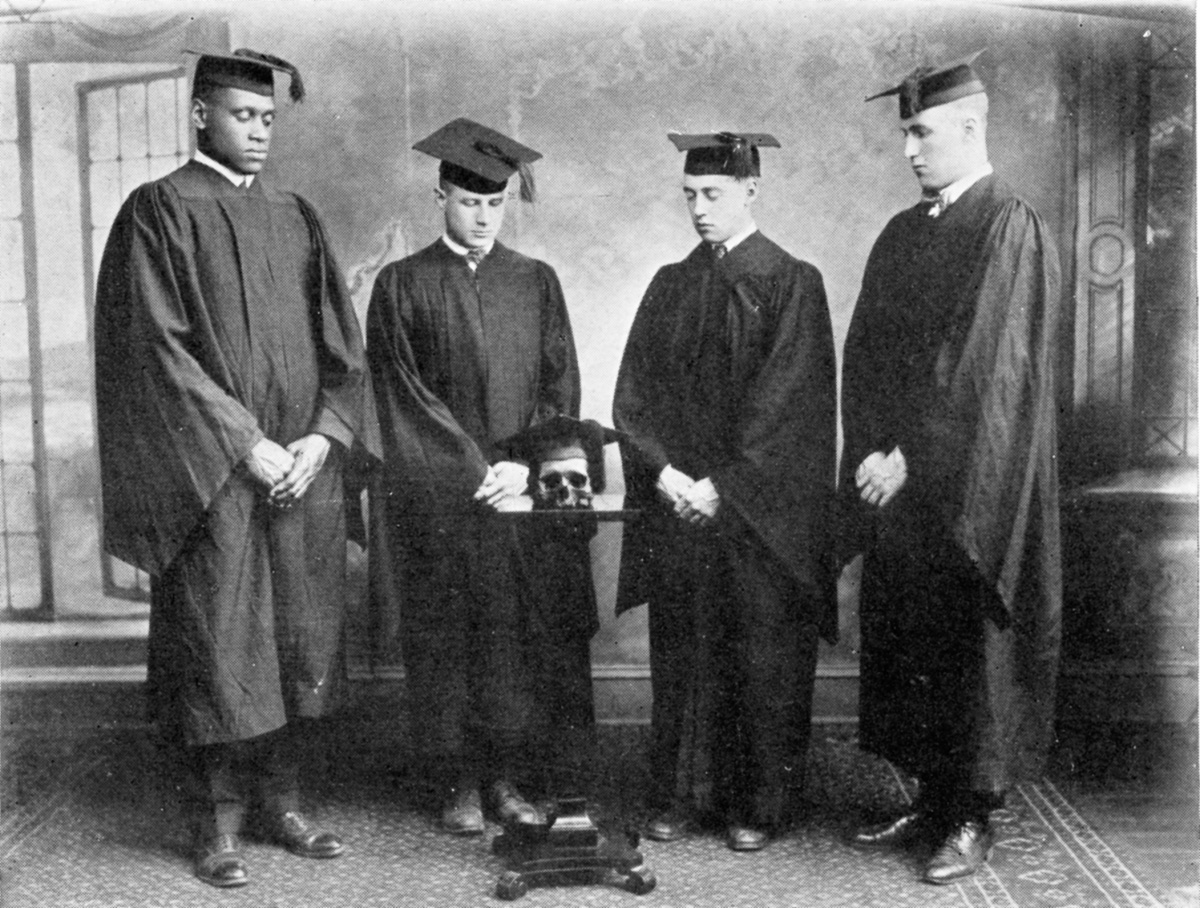

Scarlet and Black, Volume II: Constructing Race and Gender at Rutgers, 1865-1945 provides new context for the lives of Rutgers’ first African American students, the “forerunner generation” to the civil rights activists of the 1950s, 60s and 70s. The list includes Paul Robeson, the renowned entertainer and human rights activist, and James Dickson Carr, Rutgers’ first black student who graduated in 1892 and went on to Columbia Law School and a successful legal career. It also includes Julia Baxter Bates, the college’s first African American female student, who coauthored the winning brief in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, the case that declared school segregation unconstitutional.

The book also highlights lesser-known but equally notable figures, including Alice Jennings Archibald (the first black woman to obtain a graduate degree at Rutgers); Emma Andrews and Evelyn Sermons (the first black women to integrate the dorms at Rutgers’ Douglass Residential College); formerly enslaved Islay Walden (who attended New Brunswick Theological Seminary in 1876, nearly a decade before Rutgers admitted its first black student); and Edward Lawson Sr. and Edward Lawson Jr. (a father and son with Rutgers stories of racism and triumph).

Volume II examines how concepts related to race and gender evolved during the 20th century at Rutgers College and its newly created women’s college. During that time, the “Rutgers Man” and “Douglass Woman” were idealized as Anglo-Saxon, Protestant and from the middle or upper classes. Some black and other nonwhite students found opportunities to “pass” into whiteness. But others became “Race Men” and “Race Women” – they embraced race consciousness and chose to fight racism in its many forms while working to advance the status of black people in the U.S. and internationally.

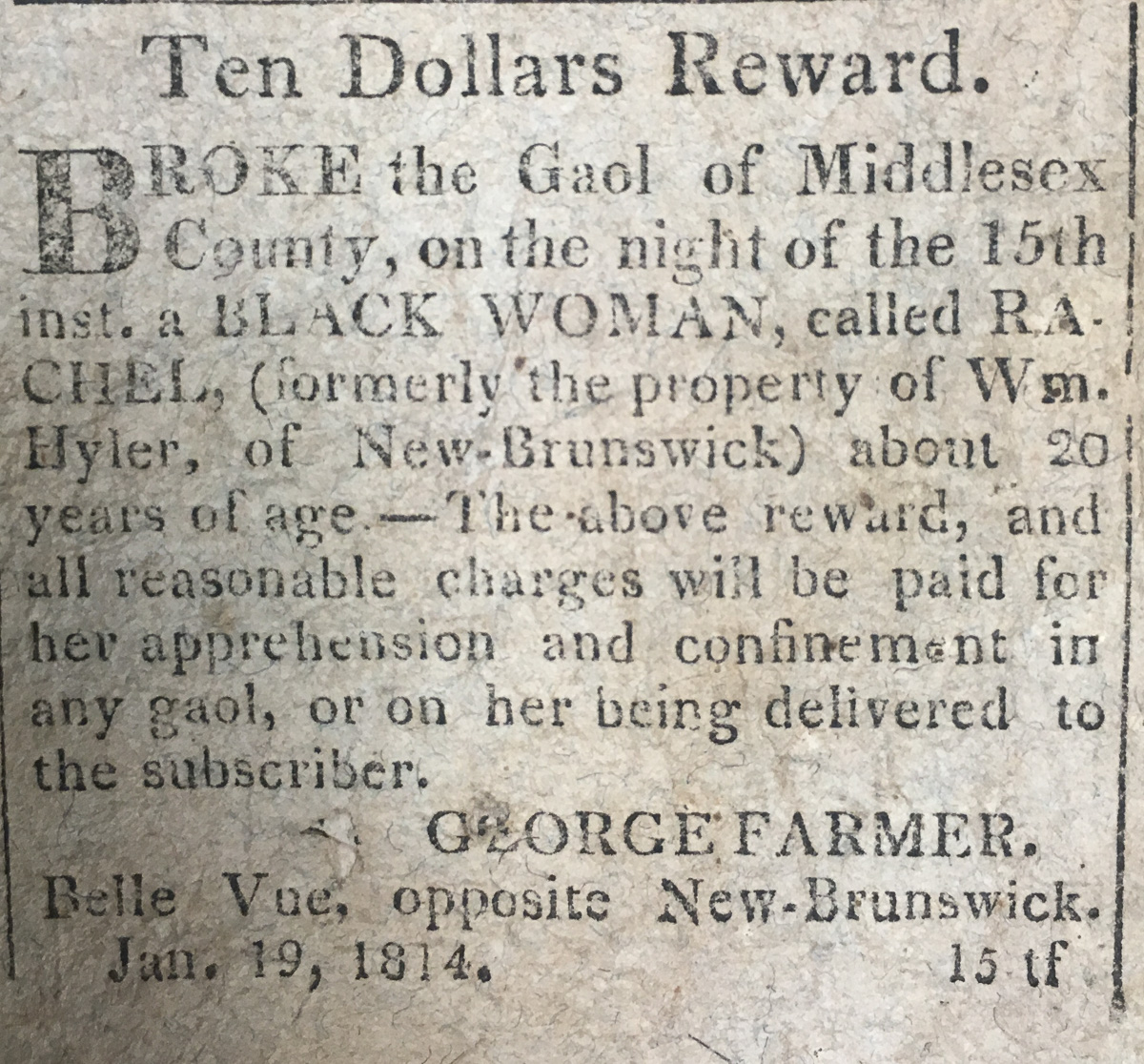

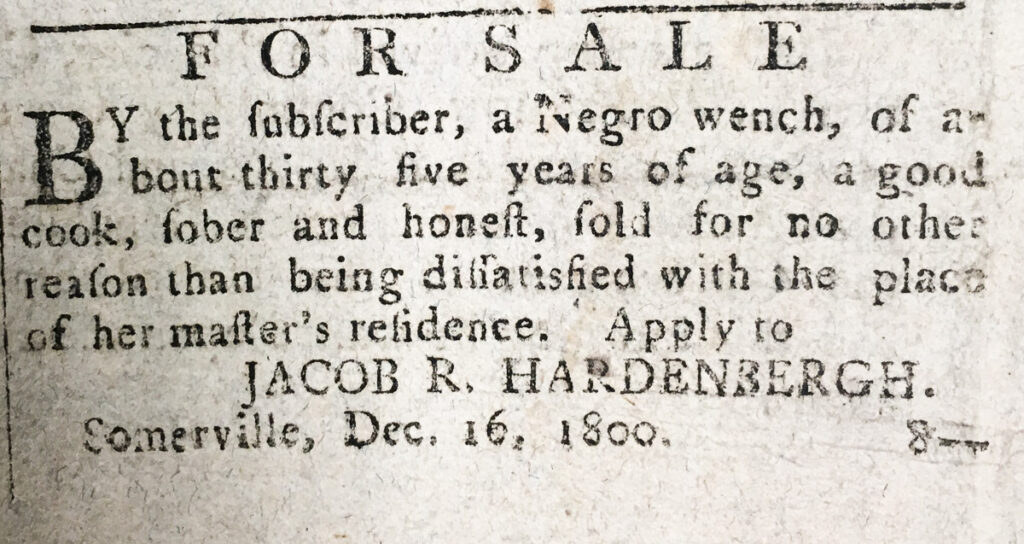

The Scarlet and Black Project, which started in 2015, is an exploration of Rutgers’ relationships with the history and legacies of racism affecting African Americans and the displacement of Native Americans from their land. The project started with 2016’s Scarlet and Black, Volume I: Slavery and Dispossession in Rutgers History, which traced the university’s early history, uncovering how the university benefited from the slave economy and how Rutgers came to own the land it inhabits. It told the story of Will, an enslaved man who helped build the foundation of the iconic Old Queens building. It also revealed that abolitionist Sojourner Truth and her parents had been enslaved by the extended family of Rutgers’ first president.

The first two volumes – as well as the upcoming third volume, which will focus on student activism and the contemporary history of students of color from World War II to the present – build on the groundbreaking scholarship of Rutgers–New Brunswick’s top graduate school ranking in African American history. A digital archive of the project’s findings can be found here.

“This January, many, if not most, in the Rutgers community celebrated the appointment of this university’s first black president, Dr. Jonathan Holloway,” said Deborah Gray White, the Board of Governors Distinguished Professor of History at Rutgers–New Brunswick and an editor of the Scarlet and Black book series.

“However, black people were not always welcomed at Rutgers. The 18th-century profits from the sale of our bodies and labor enabled the university’s existence, but we were not allowed to step on the campus as students until the late 19th century. When we were allowed to matriculate, we could not always live on campus or participate as full-fledged members of the Rutgers community. Not until the mid-20th century freedom movement did Rutgers open its doors to more than a handful of African Americans and other racial minorities, and even then, Rutgers – meaning administrators, faculty, students and surrounding neighborhoods – resisted at every turn. We are proud to add this second volume to the story of Rutgers’ journey from exclusion to inclusion. It tells the story of the first young black men and women at Rutgers, the obstacles they had to surmount and the racial climate of the classroom, university and community. We are overjoyed that this volume comes at this particular moment of new beginnings for Rutgers University.”

Marisa Fuentes, the Presidential Term Chair in African American History, an associate professor of history and women’s and gender studies at Rutgers–New Brunswick and an editor of the book, said, “The editors and authors of this volume are proud of the hard work they dedicated to publishing another substantial part of Rutgers history. As evidenced by the extensive archival research, Rutgers has not always been on the right side of history, but by acknowledging this past, we hope it’s a step forward in ensuring that all feel welcomed in the Rutgers community today. Rather than a simple indictment of the past, this work is one method of redress by recognizing how students of color have fought for a place here and have excelled. The graduate students who put in long hours of research and writing should be recognized for their commitment and rigor in telling these stories.”

The Volume II team consisted of doctoral candidates and postdoctoral fellows led by White, Fuentes and Kendra Boyd, an assistant professor of history at York University who, as a Ph.D. candidate in African American history at Rutgers, coauthored two chapters of Scarlet and Black, Volume I. The team reviewed admissions records, yearbooks, meeting accounts, personal letters and newspaper accounts to piece together the stories of the first black students at Rutgers. The university is commemorating the second volume’s publication during Black History Month and Women’s History Month, and with a March 31 public event at the Rutgers Club.

The book’s researchers and writers include Shari M. Cunningham, a Ph.D. candidate at Rutgers–New Brunswick’s Graduate School of Education. Cunningham said, “How Rutgers’ first African American students navigated the obstacles they faced on and off campus can help us to better understand the less overt but still present issues African American students in higher education are confronted with today. While progress has been made, we still face issues of inclusion and equitable representation, which must be addressed in sustainable ways moving forward.”

Volume II describes the black students who attended a Rutgers that “practiced informal Jim Crow segregation and incubated a white supremacist ideology,” according to the epilogue by White. “Their success made it possible for African American baby boomers, or the desegregation generation, to push that door wide open.”

Exploring the History of Black Women’s Experience at Douglass

With research supported by funding from Douglass College, Volume II traces the limiting ways that womanhood was defined at the beginning of the century – and how the school’s first black women helped pull Douglass toward “the multicultural world of the 21st century.” At its establishment in 1918, the school’s founders promoted opportunities in the “librarian, secretarial, nursing, domestic science, art, social and civic betterment” fields, promising it would make them “better citizens, better homemakers, better club-women” – a significant difference from the Douglass of today. Because of their gender, Douglass students at the time lived restricted lives. A college guidebook listed the restaurants they were allowed to patronize without a chaperone, many of which excluded patrons of color.

The first black women who attended Douglass found a campus culture that was beginning to challenge traditional gender roles, while continuing to reinforce racial stereotypes. A popular student publication often celebrated the “modern (white) woman” of the 1920s, juxtaposed with racist jokes and cartoons.

Though it received federal funds from a program that prohibited racial discrimination, Douglass was almost exclusively white until the 1970s. The school admitted Julia Baxter Bates in 1934 only because admissions officers thought she was white. Realizing their mistake, school administrators tried to discourage her from registering, then prohibited her from living on campus. Though she experienced discrimination at the school, Baxter later recounted the lifelong friendships she developed there. Though admissions officers had tried to discourage her from attending, “Baxter herself believed that Jewish students received harsher treatment,” the book says.

In 1946, a decade before Rosa Parks made history by sitting in the front of a bus, Emma Andrews and Evelyn Sermons became the first black women to live on campus at Douglass. They thrived on campus, and in their later careers. Sermons earned master’s degrees in education and library service at Rutgers and became a founding trustee of Raritan Valley Community College. She said Douglass let her see that “as a young woman, even as a minority woman … you can do anything you want to do.”

Volume II notes that Rutgers’ first black female students were far less likely than the first black male students to file complaints about racism on campus – perhaps because Douglass was still a new school of uncertain stability and longevity. “Race issues, even in the minds of women who experienced prejudice in the first decade of the college, might have taken a backseat to issues of gender,” the book says. “A number of black women’s experiences … propelled them to more overt race work after college, but while enrolled they kept their eyes on the prize of future opportunities.”

Alice Jennings Archibald was a New Brunswick native whose family had deep ties to the Mt. Zion African Methodist Episcopal Church, the city’s first black church and an important civic hub for African American life. She earned a bachelors of arts degree at Howard University in 1927 and an education degree from the University of Cincinnati in 1928. Unable to find work as a teacher in New Jersey, she found work in North Carolina, but her experience of job discrimination in her home state “led to a profound realization that self-determination alone would not lead to groundbreaking racial advancement.”

Archibald returned to New Brunswick a decade later to begin a career as an activist and community organizer. In 1938, she became the first African American woman to obtain a graduate degree from Rutgers, the same year as the graduation of Douglass College’s first black female undergraduate student, Julia Baxter Bates. In 1942, Archibald wrote “What the Negro Wants,” a multipoint plan for achieving economic, educational and social justice that became a blueprint for the rest of her career. Archibald became a founding member of the National Urban League of New Brunswick, which pushed Johnson & Johnson to hire black employees and the New Brunswick Public Schools to hire black teachers. The Urban League, under her leadership, pushed Rutgers’ Douglass College to let black students live on campus. It pushed for the construction of Robeson Village, New Brunswick’s first public housing complex. Archibald worked to create “a New Brunswick that lived up to what she believed it could be” and to enrich the educational, professional and cultural lives of the city’s African Americans.

Islay Walden was one of two black students admitted to New Brunswick Theological Seminary, which was closely allied with Rutgers College, in 1876. He was part of “the first black student presence on the Rutgers campus.” Walden, born into slavery and suffering a vision impairment, walked from North Carolina to Washington, D.C., and then to New Brunswick to pursue an education. In 1878, he requested a rent reduction due to financial struggles, noting that unlike his white classmates, he couldn’t earn money by preaching in a segregated church. He had created a Student Mission made up of local residents, some of whom were so destitute that Walden spent his own money to help them.

Edward Lawson Sr. entered Rutgers College in 1905. Attending Rutgers had been a lifelong dream; he even used the institution’s incoming student requirements to guide his high school studies. He thrived academically and socially at Rutgers. But he was forced to withdraw in November 1907, seven months shy of graduation, after a white janitor accused him – without evidence – of stealing mail. Lawson transferred to Howard University but continued over the years to maintain his innocence as well as positive relationships with Rutgers leaders and classmates.

His son, Edward Lawson Jr., graduated from Rutgers in 1933. His success made some amends for the injustice his father had experienced, according to the book. Lawson Jr. dedicated his career to creating better conditions for African Americans. He became a member of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Federal Council of Negro Affairs, also known as the Black Cabinet, which was a group of high-ranking African-American advisers to the president. Its creation “marked the first time that the federal government officially recognized African Americans as an interest group and that racism and discrimination might demand federal intervention.” After World War II, he joined the newly formed United Nations Division of Human Rights and, as his career drew to a close in the 1990s, he edited the Encyclopedia of Human Rights.

While describing the struggles and successes of Rutgers’ first black students, Scarlet and Black, Volume II highlights the racism they experienced, including Ku Klux Klan activity in Middlesex County, white supremacist views expressed by Rutgers faculty and racist jokes in student publications. It also explores what it meant to be a Rutgers Man and Rutgers Woman, and how black students inserted race into these gendered notions. It also takes up the issue of colorism and how the experience of light-skinned minority students, including Latinx women, was different from those with darker complexions.

White notes in her epilogue that “only a very few of the forerunners of desegregation survived to see Rutgers become the diverse institution we take pride in today. Though largely invisible, the forerunners’ legacy lives on the Rutgers campuses.”